Being unable at present to scan the cover of this book (which translates as 'Like a lost child' and is a line from his song 'Lucille' from 1969, and which incidentally has a band round it announcing 'Enfin le premier livre de Renaud' ('At last, Renaud's first book')), I use an image of Renaud's drinking place in L'Isle-sur-la-Sorgue': Le Bouchon, the French word for a (wine) stopper, among other meanings. It might seem an appropriate title for someone known as a great drinker, although by far his favourite tipple was the screw-topped 'la jaune', the yellow colour of pastis, more particularly Ricard, of which Renaud once drank about a litre a day for many years. Until, that is, he was persuaded into going teetotal after deciding that he didn't want to die, and his doctor certainly knew that he had a near fatal level of potassium in his body. The slammer Grand Corps Malade also persuaded him to come back to life and record a new album with original songs after so many years of absence, but all those thousands of letters, mostly just addressed to 'Renaud, L'Isle-sur-la-Sorgue', had a particularly strong effect on the man.

One can seek for comparisons between Renaud and other singers, particularly Francophone ones. He only mentions Jacques Brel once, but it's obvious that Georges Brassens – some of whose songs he's recorded – has been a tremendous influence. While reading this autobiography I also I found it unavoidable to make comparisons with Morrissey, who shares as many similarities with Renaud as he does differences: the never-changing left-wing stance, the champion of human rights, the hatred of authority, the defiant anarchism, the wonderful humour and observation, the brilliant lyrics, the self-derision (Morrissey writes of a nation gagging at his nakedness, Renaud calls himself 'as fat as an SNCF sandwich': irony, of course); but on the other hand Renaud may hate animal abuse but he isn't vegetarian like Morrissey, he champions the joys of fatherhood unlike Morrissey, and oh, the coyness of Morrissey's language as opposed to Renaud's.

So far this is a very roundabout way of talking about an autobiography of Renaud, but somehow it doesn't seem right to approach it conventionally, unconventional as he is. Blanche Cabanel-Seo wrote a very silly but nevertheless fascinating little book last year called Plouc toujours, a title I can only imagine best translated as 'Forever Uncool', although many years ago 'Forever a Square' would have been very appropriate, but does anyone use the word 'square' in such a context these days? Anyway, the poche version of Cabanel-Seo's book bears on the front cover a crazily-patterned pullover with reindeer: the sort of thing any remotely fashionably-minded person (OK, any normal kid) would squirm with embarrassment at the thought of wearing. And her book is full of uncool expressions, uncool behaviour, etc. But the message is in fact that we're all uncool at heart, and Cabanel-Seo is obviously in love with Renaud's words, as she borrows thirteen lines of his 'Marche à l'ombre', a song from the late seventies, and uses them on the page before the Table of Contents.

And what a song! It's not as brilliant as 'Dans mon HLM', which lists the supercool, the uncool, the spongers, the communists (sorry, I mean Trotskyists), the eccentrics who live in the narrator's HLM. No, not as brilliant, but Marche à l'ombre gives a wonderful view of Renaud at the height of his power: this song is crammed with slang, marvellous word-play, and this is Renaud's forte. It's not for nothing that Renaud, the (apparent) troubadour of the sleazy bars, the guy who writes about gangs, petty theft, the speaker of verlan (backslang), even the inventor of slang words and expressions, appears in the prestigious Petit Robert dictionary, a kind of French lexical Bible. Renaud's language is in some ways a sort of update of San-Antonio (aka Frédéric Dard) or Auguste le Breton.

But Renaud's success killed his father, or rather killed the great book that the writer Olivier Séchan believed he had in him: he was incapable of writing it. Renaud, a school drop-out without even his BEPC, had somehow captivated the youth of France, had it eating out of his hand, his words were everywhere, his face was everywhere, he was carving out his own (very exaggerated, of course) myth of Renaud the loubard, the yob of the périphérique, the cool mobylette-riding (yes, that translates as a kind of moped) nobody who is paradoxically a somebody because he's a nobody.

I'm not too sure how much influence the writer Lionel Duroy had on this book, but it's certainly not ghost-written, although at the end Renaud thanks him for following all the stages of the book's progress. And it's a hell of a story, of a kid born with a paternal grandfather who was a professor of Greek at the Sorbonne, and a maternal grandfather who was a staunch communist (and the self-confessed anarchist always had something of a soft spot for communism, as indeed the communist daily L'Humanité has, I believe, always had a soft spot for Renaud). The autobiography takes us through his marriage to Dominique and their child Lolita (or Lola), through his totally irrational belief that the KGB was after his blood, his guilt feelings, the subsequent heavy drinking and Dominique leaving him, through his second marriage to Romane Serda and their child Malone, his lapse back into alcoholism and Romane leaving him, through to (let's hope) permanent cure.

Throughout, Renaud guides us through his songs along and his life, explains the genesis of his work. What we're left with is a glorious story of a man with faults, but a real human being. OK, he might occasionally brag a bit, such as telling us that the French voted his song 'Mistral Gagnant' the all-time best French song, beating even Brel and Barbara, but so what? He's only telling the truth, and who can blame him for being proud of a lovely song? Now he's on his feet again, telling the world he's not dead and buried according to the vicious internet rumour some jerk started, but yes, there's a change. Renaud was a good friend of the people behind Charlie Hebdo, the people who were mindlessly assassinated by two no-hopers prostituting the name of Islam, so is it so surprising that the man who once called France a nation of cops, a hundred on each street corner who kill people without being punished, should, er, make a song about hugging a cop during the huge display of fraternity and defence of free speech (OK, certainly some heads of state just shouldn't have been there, but...) that the Charlie murders created?

Renaud has given many of his earnings away, and Gérard Depardieu has apparently teased him for being a fool for this, but then Depardieu is the kind person willing to change nationality when he believes he's paying too much tax, etc. Renaud doesn't criticise Depardieu because he's of course Renaud, who was in turn criticised for leaving France for London for a short time due to tax reasons, but Renaud insists that he paid via the French tax system because he has no problems contributing towards schools, roads, the general infrastructure of the country. And who can disbelieve a man whose name will certainly never appear in the Panama Papers?

Long live Renaud: a tremendous, very honest, and very generous guy.

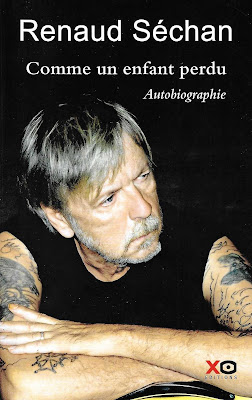

ADDENDUM: Now (with great regrets) home in England and here's the front cover of the book:

No comments:

Post a Comment